Not my house.

In an effort to keep my 4 year old son from freaking out when one of his toys breaks, we’ve started saying things like “that’s too bad, honey, but good thing you have lots of other toys!” or “that’s too bad, but it’s just a toy.” He learned his lesson so well that now, when he breaks something of mine, he will cheerfully say, “That’s okay, Mama! Good thing you have plenty of other stuff” or “remember, Mama, flowers don’t last forever.” Aargh.

For the last month or so I’ve been thinking a lot about detachment–detachment from unrealistic ideals, from expectations for the future, from the way I want things to be. As petty as it sounds, my problem with detachment from worldly things probably surfaces the most when it comes to the kids breaking my possessions. I’ve always considered myself fairly detached from material things already; it’s not like I cry when they chip my special china or something, and most of our stuff is from thrift stores anyway. But when the very few things I do care about get broken too–my only nice artwork, a gift from my father, that the kids poked holes in with a pen, and my special icon triptych from my mother, which they ripped off its hinges–I lose it. I discovered both these precious gifts while I was cleaning last week, and started ranting about how I was just fine at being detached from MOST things, but couldn’t I just have one thing that was clean and new and stylish and unbroken and modern and the right size and in the right place? Just ONE? Just how detached does God expect me to be?

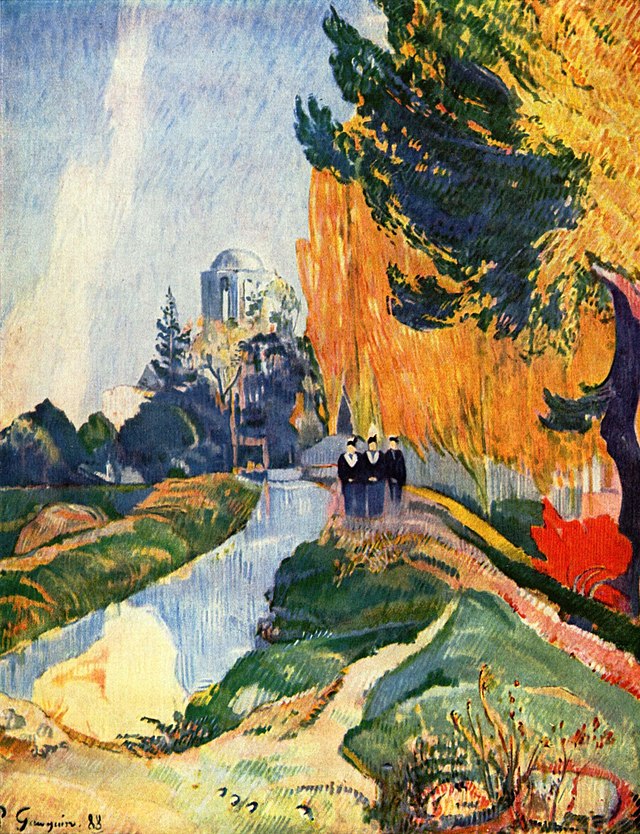

The White Veil, by Willard Metcalf.

As soon as I said that, of course, God responded by sending me lots and lots of readings about detachment. Every book I picked up, every meditation or quote in my daily Magnificat reading, was telling me how I would never get closer to God unless I learned detachment. And I really, really didn’t want to hear this. I have no idea what this means in my own state of life. I think part of my problem is that I think detachment means not caring about anything but God, but that’s not true. I’m starting to realize that what we’re really called to do (I think) is to love and enjoy the things of this world, without getting too attached. It’s more of a balancing act than I realized. After all, I need to appreciate the things that God has given me–material things, gifts, relationships, talents, and so on–and not despise them. It’s not a black-and-white choice between (a) giving everything away and sitting in a cell praying all day and (b) caring about the things I have. Instead, I think it’s a choice between appreciating the things I have as they are, broken or unbroken, and being attached to the things I have as I want them to be. If I appreciate my house only when everything’s clean and unbroken, and lose my peace when things get messed up, I’m too attached to my house. If I appreciate only the parts of my body that are to my liking, rather than appreciating the marvel that my body is right now, I’m too attached to my body. God doesn’t want me to obsess over how awful my stretch marks are, but I don’t think he wants me to say “who cares about bodies?” either. To have the proper distance from the gift that is my body, I can’t be too close (either by loving its perfections or loving its imaginary ideal) or too far (“a body is just a tool for living; who cares how it’s made or how it works or how it looks?”). (I actually did know someone like that once; he thought it was unfortunate that we had to eat. All this time we spend shoveling food into our bodies, we could be devoting to higher things, like philosophy! He was a not a healthy person.)

Thanks for listening to me think out loud. I’m obviously not sure about any of this; what do you think? All I know is that God seems to be telling me to do something that I’m terribly uncomfortable with. For the most part, I’m at peace with my stretch marks; but I’ve always been annoyed when people tell me to “embrace” them. Why can’t I just tolerate them, or ignore them? But I’m starting to get the feeling that God wants me to embrace quite a bit more.

image of monk’s cell